Tervuren Castle

Tervuren Castle (Dutch: Kasteel van Tervuren; French: Château de Tervueren) was a moated castle constructed by the dukes of Brabant, which later became a royal residence and hunting lodge for the governors of the Habsburg Netherlands. It was located in Tervuren, Belgium, just outside Brussels. It was demolished in 1782.

The park later contained the Pavilion of Tervuren, a summer palace for the prince of Orange, the future King William II of the Netherlands, which burned down in 1879. The park was used as the location of the 1897 Brussels International Exposition. Later, in 1910, the Royal Museum for Central Africa was constructed in the park, which can still be visited.

From the castle nothing remains, except some foundations. The St. Hubertus Chapel is still standing just as the stables. The park today covers an area of 207 hectares. The northern part is laid out in the French style and is characterized by a succession of ponds; the central part consists of a wooded ridge with a more natural part to the south.

History

Dukes of Brabant

Tervuren Park, also known as the Warande, was once the private hunting ground of the dukes of Brabant.[1][2] Shortly before 1213, Henry I, Duke of Brabant settled in Tervuren, and constructed a castle within the park. It was completely surrounded by water – the so-called 'Borgvijver', currently the 'Sint Hubertusvijver'.[1][2] The castle was primarily used as a hunting lodge and developed over time into a beautiful and favourite ducal residence, especially in summer.[1][2] Henry I also constructed his own church near the castle, dedicated to John the Evangelist, which is now the current parish church of Tervuren.[1][2]

Until 1430, the residence was regularly inhabited, fortified, expanded and transformed into a prestigious ducal retreat.[1][2] 16th and 17th century engravings show a fully enclosed complex with walls and towers, connected to the village by a drawbridge.[1][2] The complex was dominated by a large Gothic hall (48 by 18 metres), constructed by Duke John II, similar to the Ridderzaal in The Hague and Westminster Hall in London.[1][2] The hall was used as a meeting room for the States of Brabant and as centre of large festivities and hunting parties.[1][2] In the last part of his life, Duke John III spent most of his time at Tervuren Castle.[1][2] He transferred part of his administration to the castle.[1]

In the start of the 15th century, the dukes of Brabant from the House of Burgundy regularly stayed at the castle.[1] Two dukes are also buried in the parish church of Tervuren, Duke John IV and Duke Philip I.[1] After 1430, the absence of the dukes of Burgundy heralded the decline of the castle and the village.[1] The park around the castle was first only 10 hectares, but was considerably expanded over time.[2]

-

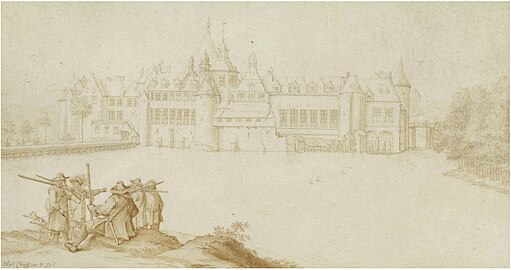

Tervuren Castle around 1604–1605 before the reconstructions by Archdukes Albert and Isabella

Tervuren Castle around 1604–1605 before the reconstructions by Archdukes Albert and Isabella -

Hunts of Maximilian tapestry with Tervuren Castle in the back (1531)

Hunts of Maximilian tapestry with Tervuren Castle in the back (1531) -

Tervuren Castle around 1608 by Denijs van Alsloot

Tervuren Castle around 1608 by Denijs van Alsloot

Albert and Isabella

With the arrival of the archdukes Albert of Austria and Isabella Clara Eugenia in the period 1599–1633, the dilapidated castle site experienced a new impetus.[1][2][3] From 1610, the feudal castle was transformed by the court architect Wenceslas Cobergher into a country residence as known from the many prints, drawings and paintings by Peter Paul Rubens, Jan Brueghel the Elder and Denis van Alsloot, among others.[1][2] The old corner towers and the Gothic hall were preserved, while the disparate medieval volumes were replaced by elongated Renaissance wings with high cross windows, dormer windows and covered galleries.[1][2] On the forecourt, the still existing St. Hubertus Chapel (1616–17) was erected to replace the wooden "Sint-Huybrechtscapelle".[1][2] The castle's immediate surroundings were embellished with a "motte" in the Borg pond—a square parterre structure with corner arbors connected to the solid ground by bridges—and with geometrically laid out ornamental gardens.[1][2] The Warande was opened up by straight lanes.[1][2]

In the same period, the area was significantly expanded, including part of the hamlet of Goordal and the old banmolen of the dukes of Brabant, also known as the "Spanish house".[2] In 1625–1632, the wooden palisade was replaced by a seven kilometres long brick wall with ten gates, of which important remains are still preserved.[2] A painting by Jan van der Heyden dating from around 1700, with a view of the castle from the south, shows the wall on the west side of the Warande with the Leuvensepoort on the right.[2]

After Albert and Isabella, decline set in again.[1] From 1689 to 1708, Olympia Mancini, Countess of Soissons, niece of Cardinal Mazarin, who had been exiled from France, stayed at Tervuren Castle.[1]

-

Archduke Albert with Tervuren Castle in the back by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder

Archduke Albert with Tervuren Castle in the back by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder -

Tervuren Castle in 1659 by Sanderus

Tervuren Castle in 1659 by Sanderus -

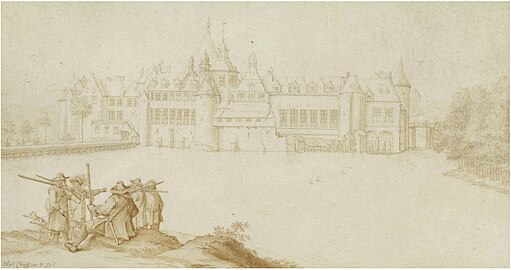

Hunters resting in front of Tervuren Castle

Hunters resting in front of Tervuren Castle

Charles of Lorraine

After the death of the archdukes, the residence was only sporadically inhabited and there is even extensive neglect.[1][2] This came to an end with the new governor of the Netherlands, Archduchess Maria Elisabeth, who, after her visit to Tervuren in 1725, ordered the court architect Jean-André Anneessens to completely restore the castle, an assignment that he retained under her successor Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine.[1][2] After his death in 1754, the works were continued by the Bruges architect Jean Faulte, mentioned in 1757 as "Directeur des ouvrages de Tervueren".[1][2]

Charles of Lorraine developed an enormous construction activity in Tervuren.[1][2] In line with the spirit of the times, the castle was opened up into an airy 18th-century summer residence and extended on the east side with a new wing, as can be seen on a map (1773) by Laurent-Benoît Dewez.[1][2] A monumental entrance was created on the west side of the Warande in the form of a spacious, horseshoe-shaped stables and maid complex, followed by a new lane (currently the 'Kasteelstraat') as a direct connection between the castle and the village centre.[1][2] The arched wings of the horseshoe housed the horses and carriages, and the main servants lived in the two symmetrical corner pavilions.[1][2] From 1897 to 2014, the 'Horseshoe' was used by the Belgian army as the 'Panquin' barracks.[1][2]

To the right of "het Hoefijzer", on the south side, a spacious orangery and a botanical garden were planted, with a large dog kennel a little further on; on the left, on the north side, a vegetable garden surrounded by a falconry, a silkworm farm and a pheasant farm.[1][2] To the south of the castle, a terraced pleasure garden was created, embellished with fountains, vases, statues, a labyrinth, toys, a bathing pond with artfully painted Chinese pavilions, a cascade, an aviary for exotic birds, all connected by steps and leafy tree galleries.[1][2]

The Warande itself also received a thorough facelift and the original checkerboard pattern was changed into a star-shaped layout, with the various avenues converging in the 'Zeven window'.[1][2] Between 1755 and 1760, an 80-metre-wide, arc-shaped industrial complex arose on the dam of the Goordalvijver, which, as a counterpart to the Hoefijzer, formed the eastern terminus of an elongated visual axis.[1][2] Borchtvijver and Goordalvijver were connected by a canal so that Charles of Lorraine could sail from the castle to the workshops by gondola.[1][2] This factory, an elongated classicist building with central and corner pavilions, in which various new techniques were tested, included workshops for machine building, porcelain, wallpaper, a printing house, weaving mill.[1][2] All this splendour has been extensively documented, including an anonymous plan from 1760–1770, the Ferraris map (1770-1778), the pen drawings N. De Sparr (1753) and the descriptions in the "Guide Fidèle" (1761).[2]

At the end of his life, in 1778, Charles of Lorraine decided to construct a new palace in Tervuren, the Château Charles, which only had short existence, as it was soon demolished in 1782. [4]

-

Tervuren Castle in the time of Charles of Lorraine by Heylbrouck

Tervuren Castle in the time of Charles of Lorraine by Heylbrouck -

Tervuren Castle in the time of Charles of Lorraine by Heylbrouck

Tervuren Castle in the time of Charles of Lorraine by Heylbrouck

Demolition

Charles of Lorraine died in 1780.[1][2] To pay off the debts left by Charles, his nephew Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor decided 1781 to demolish both Tervuren Castle and the Château Charles, which ultimately happened in 1782.[1][2] Only the St. Hubertus Chapel and the Hoefijzer were spared from demolition.[1][2] From the castle, only some foundations remain, which were subject to an archaeological investigation between 1982 and 1986.[2] Today, they is an archaeological site within Tervuren Park.[2]

William II: Pavilion of Tervuren

For his participation at the Battle of Waterloo, Tervuren Park was donated to William, Prince of Orange.[1][2] He constructed a neoclassical pavilion for himself and his family on the northwestern edge of the Warande; this pavilion was destroyed by fire in 1879 and was not rebuilt.[1][2] The accompanying ice cellar was preserved.[1][2]

After the Belgian Revolution in 1830, the pavilion, together with the entire Tervuren Park, became the property of the Belgian State.[1][2] Under Leopold I, the eldest son and heir to the throne, Leopold II was allowed to use the pavilion and park.[1][2] Under Leopold II, who had a special fondness for Tervuren and at one point even considered living there permanently, the Warande was further expanded through targeted purchases.[1][2]

World Exhibition of 1897

Decisive for the further evolution and survival of the Warande, however, was the fact that, at the instigation of Leopold II, the 1897 Brussels International Exposition took place simultaneously in Brussels and Tervuren.[1][2] There, the Congo Free State's prosperity was brought to the public's attention.[1][2] To make the colonial exhibition attractive and accessible, Tervuren was connected to the capital with a wide, 11 km (6.8 mi) tree-lined avenue, flanked by a tram line, which was constructed for the occasion.[1][2] At the end of this avenue, on the site of the burnt-down pavilion, the Palace of Colonies was built, designed by the architect Ernest Acker.[1][2] The pavilion was intended as an exhibition space and was framed by classical French gardens with ponds, staircases and statues designed by the French landscape architect Elie Lainé.[1][2] Lainé became well known in the 1870s as the designer of the garden at Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire, England, commissioned by Ferdinand de Rothschild.[1][2] He was exponent to the growing interest in Le Nôtre-styled gardens, which would see a revival mainly due to Henri and Achille Duchêne.[1][2]

Royal Museum for Central Africa

Due to its success, the Palace of Colonies has been a museum since 1898.[1][2] However, the available space soon proved insufficient, so Leopold II decided on 3 December 1902 to expand it so Chinese and Japanese exhibitions could be shown.[1][2] The project was completed thanks to subsidies from the Congo Free State.[1][2] The French architect Charles Girault, whose Petit Palais was liked by Leopold II at the Paris Exposition of 1900, was commissioned to develop a concept that encompassed the entire Lokkaartsveld along the Leuvensesteenweg, including of the Palace of Colonies site.[1][2] In addition to a museum, the project would have also built an international conference center and a school.[1][2] Following the death of Leopold II, however, only the Congo Museum, the current Royal Museum for Central Africa, would be realized.[1][2]

-

The entrance to Tervuren Castle

The entrance to Tervuren Castle -

The horseshoe stables today

The horseshoe stables today -

-

St. Hubertus Chapel

St. Hubertus Chapel -

Remains of Tervuren Castle

Remains of Tervuren Castle

See also

Other residences used by Charles of Lorraine:

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be Wijnants, Maurits (1997). Van hertogen en Kongolezen. Tervuren en de Koloniale tentoonstelling 1897 (in Dutch). Tervuren: Koninklijk museum voor Midden-Afrika. p. 184. ISBN 90-75894090.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf "The Warande in Tervuren". www.onroerenderfgoed.be (in Dutch). 5 June 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ Liesenborghs, Philippe. "Het edele vermaak. De jacht in de Spaanse Nederlanden onder de Aartshertogen". www.ethesis.net (in Dutch). Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ Derveaux, Elisabeth; Breugelmans, Annemie (2012). Karel van Lorreinen (Lotharingen) & Tervuren : Lunéville 1712 - Tervuren 1780 (in Dutch). Tervuren: Koninklijke Heemkundige Kring St-Hubertus (Tervuren). p. 95.

Literature

- Davidts, Juul Egied (1981). Het Hertogenkasteel en de Warande van Tervuren (in Dutch). Tervuren: Gemeentebestuur Tervuren.

- Everaert, L (1992). "De architecten van Karel van Lotharingen en Tervuren". De Woonstede (in Dutch): 4–17.

- Hermant, Cécile (1997). "Les aménagements du domaine de Tervueren et le« château Charles » sous Charles de Lorraine, gouverneur général des Pays-Bas autrichiens (1749-1780)". In Mortier, Roland; Hasquin, Hervé (eds.). Études sur le XVIIIe Siècle XXV Parcs, Jardins et Forêts au XVIIIe Siècle. Éditions de l'Université de Bruxelles. pp. 111–144.

- Wijnants, Maurits (1997). Van hertogen en Kongolezen. Tervuren en de Koloniale tentoonstelling 1897 (in Dutch). Tervuren: Koninklijk museum voor Midden-Afrika. p. 184. ISBN 90-75894090.

- Dumortier, Claire; Habets, Patrick, eds. (2007). Bruxelles-Tervueren Les ateliers et manufactures de Charles de Lorraine (in French). Bruxelles: CFC Editions. ISBN 978-2-930018-64-5.

- Derveaux, Elisabeth; Breugelmans, Annemie (2012). Karel van Lorreinen (Lotharingen) & Tervuren : Lunéville 1712 - Tervuren 1780 (in Dutch). Tervuren: Koninklijke Heemkundige Kring St-Hubertus (Tervuren). p. 95.