May 1921 geomagnetic storm

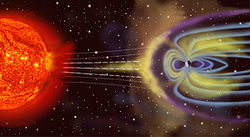

Artist's depiction of solar wind striking Earth's magnetosphere (size and distance not to scale) | |

| Geomagnetic storm | |

|---|---|

| Initial onset | 13 May 1921 (1921-05-13) |

| Dissipated | 15 May 1921 (1921-05-15) |

| Peak Dst | −907±132 nT |

| Impacts | Substantial damage to overhead and underwater telegraph equipment; electrical fires; localized electric grid interruptions |

Part of solar cycle 15 | |

The three-day May 1921 geomagnetic storm, also known as the New York Railroad Storm, was caused by the impact of an extraordinarily powerful coronal mass ejection on Earth's magnetosphere. It occurred on 13–15 May as part of solar cycle 15, and was the most intense geomagnetic storm of the 20th century.[1]

Since it occurred before the extensive interconnectivity of electrical systems and the general electrical dependence of infrastructure in the developed world, its effect was restricted; however, its ground currents were up to an order of magnitude greater than those of the March 1989 geomagnetic storm which interrupted electrical service to large parts of northeastern North America.[2]

Effects

The storm's electrical current sparked a number of fires worldwide, including one near Grand Central Terminal which made it known as the "New York Railroad Storm".[1] Contemporary scientists estimated the size of the sunspot (AR1842)[1] which began on May 10—and caused the storm—as 151,000 by 34,000 km (94,000 by 21,000 miles).[3][4]

The storm was extensively reported in New York City, which was a center of telegraph activity as a railroad hub.[5] Auroras ("northern lights") appeared throughout the eastern United States, creating brightly lit night skies. Telegraph service in the U.S. first slowed and then virtually stopped at about midnight on 14 May due to blown fuses and damaged equipment.[6] Radio propagation was enhanced during the storm due to ionosphere involvement, however, enabling unusually good long-distance reception. Electric lights were not noticeably affected.[7]

Undersea telegraph cables were affected by the storm. Damage to telegraph systems was also reported in Europe[8] and the Southern Hemisphere.[9]

Comparison to other geomagnetic storms

In space weather, the disturbance storm time index (Dst index) is a measure often used for determining the intensity of solar storms. A negative Dst index means that Earth's magnetic field is weakened—particularly the case during solar storms—with a more negative Dst index indicating a stronger solar storm.

A paper in 2019 estimated that the May 1921 geomagnetic storm had a peak Dst of −907±132 nT.[10]

For comparison, the Carrington Event of 1859 had a peak Dst estimated to be between −800 nT and −1750 nT.[11] The March 1989 geomagnetic storm had a peak Dst index of −589 nT.[12]

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b c Phillips, Tony (12 May 2020). "The Great Geomagnetic Storm of May 1921". spaceweather.com. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ Dr Tony Phillips (January 21, 2009). "Severe Space Weather - Social and Economic Impacts". NASA. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ "Borealis Cause, Sun Spots, Will Diminish Today" (PDF). Chicago Daily Tribune. May 16, 1921. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "Sun Spots Vanishing" (PDF). The Los Angeles Times. May 16, 1921. pp. 1 & 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "May 13, 1921 – The New York Railroad Storm". SolarStorms.org. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ M. Hapgood (2019). "The great storm of May 1921: An exemplar of a dangerous space weather event". Space Weather. 17 (7): 950–975. Bibcode:2019SpWea..17..950H. doi:10.1029/2019SW002195.

- ^ "Sunspot Aurora Paralyses Wires" (PDF). New York Times. May 15, 1921. pp. 1 & 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 22, 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "Cables Damaged by Sunspot Aurora" (PDF). New York Times. May 17, 1921. pp. 1 & 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "Aurora Borealis". Hawera & Normanby Star. May 16, 1921. p. 8. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ Jeffrey J. Love; Hisashi Hayakawa; Edward W. Cliver (2019). "Intensity and Impact of the New York Railroad Superstorm of May 1921". Space Weather. 17 (8): 1281–1292. Bibcode:2019SpWea..17.1281L. doi:10.1029/2019SW002250.

- ^ "Near Miss: The Solar Superstorm of July 2012". NASA Science. Archived from the original on 11 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ Boteler, D. H. (10 October 2019). "A 21st Century View of the March 1989 Magnetic Storm". Space Weather. 17 (10): 1427–1441. Bibcode:2019SpWea..17.1427B. doi:10.1029/2019SW002278. ISSN 1542-7390.

Bibliography

- The Aurora Borealis of May 14, 1921 JSTOR 40710695

- "May 13, 1921 – The New York Railroad Storm". Solarstorms.org. Retrieved February 9, 2019. A bibliography of newspaper and journal articles.

- "Northern Lights Are Busy" (PDF). New York Times. May 14, 1921. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "Aurora Borealis Halts Telegraph Service to City" (PDF). The Atlanta Constitution. May 15, 1921. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- Henry K. Bunn (May 15, 1921). "The Story The Week Has Told" (PDF). The Atlanta Constitution. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "Tricky Aurora Snarls Up Wires" (PDF). Chicago Daily Tribune. May 15, 1921. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "Aurora is Disturber" (PDF). The Los Angeles Times. May 15, 1921. pp. 1 & 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "The Aurora Borealis" (PDF). The Los Angeles Times. May 16, 1921. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "Aurora Borealis Effect on Wires Laid to Sun Spot" (PDF). The Atlanta Constitution. May 16, 1921. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "Sunspot Credited with Rail Tie-Up" (PDF). New York Times. May 16, 1921. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "Magnetic Tremors Expected to Pass Within 48 Hours" (PDF). New York Times. May 16, 1921. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "Cables Still Show Effects of Aurora" (PDF). New York Times. May 18, 1921. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "Electric Disturbances Affect French Wires: Aurora Not Visible, Its Absence Being Attributed to Atmospheric Conditions" (PDF). New York Times. May 18, 1921. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "Magnetic Storms Don't Affect Radio" (PDF). New York Times. May 26, 1921. p. 23. Retrieved December 19, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- S.M. Silverman; E.W.Cliver (March 2001). "Low-latitude auroras: the magnetic storm of 14–15 May 1921". Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics. 63 (5): 523–525. Bibcode:2001JASTP..63..523S. doi:10.1016/S1364-6826(00)00174-7. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- v

- t

- e

| Solar atmosphere | |

|---|---|

| Interplanetary space | |

| Magnetosphere | |

| Planetary atmosphere | |

| Related |

| |||||||||||||